By Lonneke Peperkamp and David Whetham

The horrendous attack by Hamas and related militants on Israel must be unequivocally condemned. In the early morning of October 7th, militants launched thousands of rockets, took hostages, and slaughtered innocent civilians in their homes, a festival and in the streets. The deliberate and widespread killing of civilians in a brutal attack violates the most basic moral and legal principles. These same principles affirm Israel’s inherent right to self-defence, allowing them to respond to the threat posed by Hamas with military force.

It is also clear that the ongoing hostilities over the last weeks have had devastating effects, with Palestinian civilians being killed, trapped under collapsed buildings, injured and forced to flee. Israeli air strikes have exacerbated already miserable living conditions associated with the ongoing blockade, resulting in a dramatic escalation of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, and there is much focus on alleged breaches of the rules of war and charges of collective punishment being employed as a de facto policy. The international community is calling for restraint and the sorrow, trauma, and immense suffering endured by all those affected are beyond imagination for most of us.

The facts on the ground, the dynamics of this conflict, its complicated history, profound and entrenched injustices, the legal implications – all are subject to an intense and polarized public debate, often fuelled by strong emotions. How can we discuss these issues in moral terms? Grief, trauma, and shock can easily lead to framing the conflict as a struggle between ‘good’ and ‘evil’, with assumptions that in the face of evil, one is obliged to act regardless of the consequences. History shows that when terrible wrongs have been inflicted on a community and its people, this can lead to a diminished concern for the harms committed in response because the other side “started it”. Consequently, any harms are attributed to the other side rather than our own, as we identify ourselves as the injured party.

If one’s cause is just, why should the righteous be treated the same as the unjust? (1) Why would the side that is in the right not be permitted to do whatever is required to win? Especially if the enemy does not seem to care about the rules, slaughters civilians, and uses its own population as human shields? Or, if the military superiority of the enemy cannot be confronted by “playing by the rules”? Pointing out and isolating the wrongs committed by the enemy can become an excuse for disregarding one’s own moral obligations.

Within the canon of thought on the ethics of war, there exists a distinction between the jus ad bellum (what is required to justify going to war) and the jus in bello levels of war (what can legitimately be done within a conflict once it has started). This distinction between the two levels of conflict, in theory, in law, and to a good degree in practice, allows us to draw a line of moral responsibility between the decision to go to war and the actual conduct of that war. Fighters on either side are not necessarily responsible for the decision to send them to war. However, they are responsible for the actual conduct of the war—fighting it in a legitimate way. And that means protecting humanity in the face of war.

Whatever the objective rights and wrongs of the conflict, and regardless of whether fighters believe their cause to be just, there are no special freedoms or permissions granted to one side over the other. Whilst this distinction between the levels of conflict has been challenged in philosophical circles, the hostilities between Israel and Hamas underline the importance of these equal legal norms—after all, both sides will claim they are the ones in the right. Limiting harm to innocent civilians therefore requires that all fighters fight within the rules, regardless of whether one fights on the “right” side, or whether the other side flouts or ignores every rule in the book.

Attempts to argue for moral equivalency, to see morality as zero-sum, or to measure and compare the degree to which different heinous acts outrage the common decency of mankind miss the most important point. Most urgent now is the limitation of suffering. Hostages must be released and both Palestinian and Israeli civilians must be protected far better than they have been in the past weeks. For that, we need restraint, and we should not lose sight of our shared humanity. And that is difficult. History shows us that passion, hatred and enmity for what “they” have done make such restraint the hardest thing imaginable to contemplate or practice. But replicating wrongs done or creating new ones as a form of punishment does not provide safety and security – in the short term or long term.

Footnote

(1) The following section partly builds upon a previous publication of one of the authors: Whetham, David (2017) "My Country, Right or Wrong: If the Cause Is Just, Is Anything Allowed?," The International Journal of Ethical Leadership: Vol. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/ijel/vol4/iss1/5

About the authors:

Lonneke Peperkamp is Professor of Military Ethics and leadership at the Netherlands Defense Academy, and affiliated with iHub (Radboud University Nijmegen) and King’s Centre for Military Ethics. She is vice president of EuroISME, the International Society for Military Ethics in Europe.

David Whetham is Professor of Ethics and the Military Profession at King’s College London, based at the Joint Services Command and Staff College. He is Director of the King’s Centre for Military Ethics and is vice president of EuroISME, the International Society for Military ethics in Europe.

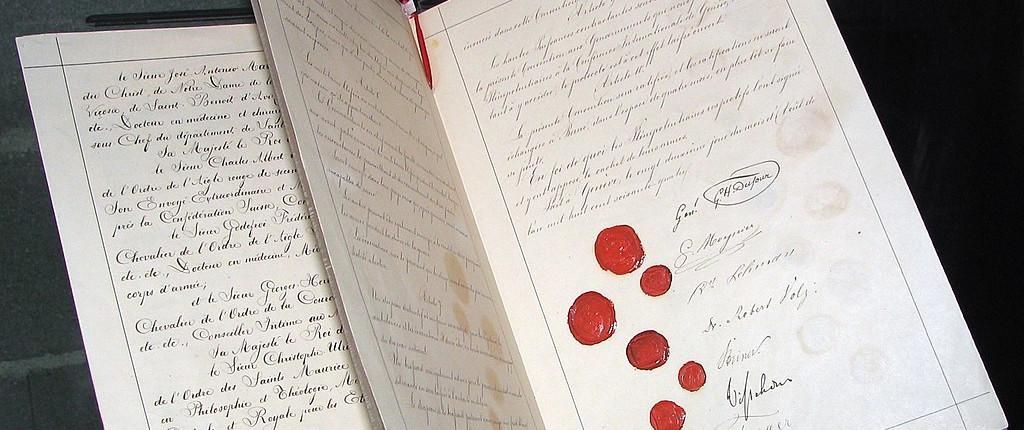

Picture Credit: Kevin Quinn, Ohio, US, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Comments

By Daniel Beaudoin, 01 Dec 2023

I would encourage the authors to reconsider labeling Hamas a militant group. A perfunctory reading alone of the Hamas charter should suffice to convince even the most hardened sceptics that Hamas is a terrorist organization. Consider, that even the EU (and that says a lot) has listed Hamas as a terrorist entity. Moreover, what else can you name an organization that beheads babies, burns mothers alive, butchers parents in front of their children, rapes and kills young women, and then then parades the bodies in Gaza where Palestinian citizens spit on them and mutilate them, where babies are held hostage and separated from the their mothers as they are stowed away underground in one of the tunnels of the 500 km network that Hamas has built under the citizens in the Gaza strip, and using these citizens as human shields, in order to draw the ire of the world when Israel returns fire.

Words matter, and as Wittgenstein already said, the limits of my language are the limits of my world. Any consideration of the moral and ethical dimensions of this conflict must take these words into account, and the reality that they represent.